Healing Is A Fluid Journey: How Hurricane Katrina Changed Me

Aug. 26, 2005, gave me everything that a Friday night could give.

My girls and I fell into a poetry night at a dark, sexy club, as girls our age did in a post- Love Jones society. Joy dominated the room. This is not my mind playing a trick, as I remember the before times. The room was energized by the call-and-response and lingering hugs that felt like home and community.

Peaches was still alive. She told me it was time to stop playing scared and write for more than just me. I hugged her. Neither of us knew it was for the last time. We hopped to another club. I was wining on a very fine man who my friends said looked like “your kind of foolishness.”

It was the type of night that made me feel like opting out of my relocation plan to D.C. the month before was the right choice. There isn’t a thing I would have changed about that night. It just would have been nice to know that New Orleans had just served me a last meal of sorts.

I woke up with a hangover and two missed calls from my daddy, asking what my hurricane plan was, because this storm was really coming. I half listened to a news report about a storm, but in my 28 years, that promise had yet to materialize. Remembering the huge and embarrassing argument we got into while we evacuated during Hurricane Ivan in 2004 — a stressful round trip that I couldn’t afford with a 4- and a 6-year-old — I revealed that my plan for the storm was no plan at all. “Baby, I’ll give you whatever you need. Grab what you can because we’re leaving tonight. We don’t want to be on these roads tomorrow.” Not tomorrow. Tonight. They always spoke with urgency about hurricanes. Daddy did not.

I scraped my coins together and filled up “Big Pimpin’,” my 1991 Celica with 228,000 miles and a winky headlight named after the first song that played on the radio when I bought it. Again, remembering how I overdid it for Hurricane Ivan, I grabbed only a weekend’s worth of clothes and our vital documents. At the last minute, I put the kids’ toys in a sealed Rubbermaid container and told them, “This way, if water gets in the house, your toys will still be dry.”

We would never see those toys or the inside of that apartment again. After an uneventful drive, my family — me, my two kids, my sister, my parents, my grandmother, and two aunts — pulled into Shreveport in the early morning hours, dispersed among another sister’s in-laws and friends. Sunday brought with it a grim reality: the storm was not turning.

“Every Katrina you know who spells it with a K ain’t nothing nice,” my girlfriend would later say, and she was right. And it is Katrina. Not Hurricane Katrina; as though she is a who, and not a what. A vile creditor who came to collect and decided that the cost was at her discretion.

Here is where I need a line. Something as thick and clear as the ones Nash Roberts drew every hurricane season, tracking who I was before and after Aug. 29, 2005. Instead, my memory of that week looks like it was underwater too; smudged and murky. I guess we can add my ability to sequence the events of that week to the list of things that she took. But I’ll never forget Mississippi.

Before there was clear reporting about what was happening in New Orleans, I was fixated on the flooding in Mississippi. To say that people were distraught feels inadequate. I don’t know if you can address that type of compounding grief with only one word.

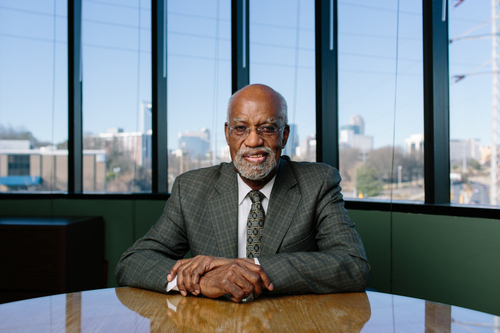

I still remember Mr. Hardy Jackson’s rapid breathing as he explained that the stormwater carried his wife, Tonette, away. “You can’t hold me. Take care of the kids and the grandkids.” Mrs. Jackson’s remains wouldn’t be identified until 2024, 11 years after Mr. Jackson’s death.

Though Mississippi’s story and experience are not mine to tell, it is not a story that we should ignore or dismiss as some other thing. It is all the same tragedy, and in one way or another, we all share the kinship of being failed.

There was some discrepancy over who knew what and when they knew it. The news that I watched did not definitively address the levee breaches until Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2005. The aerial shot dropped me to my knees. When I could finally find my voice, my words came out in a confusing tumble. Everyone who stayed behind was trapped in the heat, or the filth, or a horrific August combination of both. Help was slow, as was food and water. But naked racial bias was right on time.

We saw clear as day imagery of white New Orleanians being labeled as “finding food,” while Black New Orleanians were called looters. The president and FEMA officials high-fived themselves and each other as people, primarily Black, begged for food and water. As we scratched out lives in other places, we were given all manner of undesirable labels.

Just recently, I cringed as I watched The Boondocks episode “Invasion of the Katrinians,” which left the nuance of our trauma unaddressed. Isn’t it funny how white people get to be expatriates, but just a bit of melanin turns you into a refugee? I looked at my community, a sea of people from whom I was likely only removed by three degrees at most, who were hurting, and knew that when I came back, it would be as an asset.

I can hear you wondering, “Why didn’t they evacuate?”

Louisiana has the highest poverty rate in the nation, sitting at 18.9%. The poverty rate in New Orleans is 22.6%. Even with two children, I lived above the poverty line and was only able to leave because I had a daddy with available credit. When we hear words like “living wage,” it isn’t just an abstract concept. It literally means having the means to survive when life throws you hurricane-sized curve balls.

Support in all forms came to me from friends and strangers, and my community expanded. So much aligned in my favor that guilt hitched a ride on my rage. How did I think I had the right to any feeling but gratitude? I had a warm bed. I had food. Because I received support, I didn’t count what I experienced as “real” loss. I had to get my butt up and make chicken salad out of this chicken…you know the rest.

A scrapped plan is still a plan, so I set up a series of interviews in D.C. I was a legal secretary with experience, great recommendations, and a well-known sad story that I didn’t even have to tell. I was placed almost immediately. My place in Silver Spring, Maryland, was idyllic and homelike.

That fall was only the second time I witnessed a true autumn with colorful leaves. I fell in love with snow and in hate with ice. My life resembled a life with friends and traditions. I was fine. Great even for a girl living in a place that was homelike, even though it wasn’t home.

I went back home by flying in through Gulfport International Airport for the first time in February 2006, before Armstrong International was operating again. The first thing I noticed on the drive home was the trees. The bald cypress and live oak trees that shaded so many drives to and from Biloxi looked like broken matchsticks. The Twin Span, ravaged by the intense wind and water, was a patchwork horror to me, a woman who is terrified of bridges.

As I rolled around the city with my stepmom, we went to the reopened Lakeside Mall, where I bumped into the lady who sold me donuts at the McKenzie’s when I was little. I was not great. I was not fine. We stood there and hugged, because it had been five months since I ran errands and bumped into someone I knew. My memory tells me that I held it together and didn’t cry, but I don’t know if that’s true.

The corruption and generalized lack of care that was pervasive in New Orleans and contributed to this failure took a toll on us all. In the years that followed, it would be exposed to everyone. Public figures were indicted and arrested, and some were incarcerated. Institutions such as the public school system were revamped. Yet with all this change, New Orleans will find a way to be New Orleans, flaws and all. Nevertheless, we persist. My visits home became less frequent, and the city I returned to each time became less familiar.

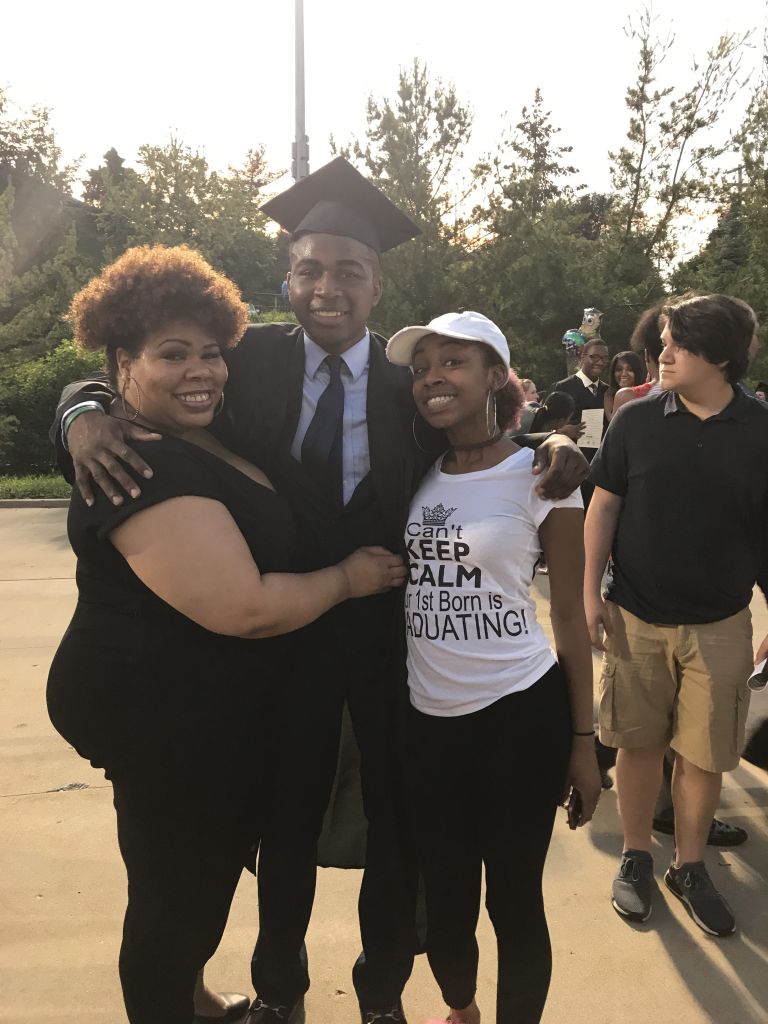

Life happened for my children as well. Being so young when we evacuated, they became themselves on “foreign soil.” They experienced their own wins and losses and formed their own stories. I won’t presume to tell their story for them. From my perspective, I was “a single mom with two kids.” But they are two human beings and are being shaped by their own experience. And each of them came to the conclusion that they are not New Orleanians, which pains me. Our second relocation was to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It is charming and homelike, but not home to me; yet home for them.

In the 20 years that have now passed, and the 15 years that I was away, I searched for myself, gathering fragments here while losing others there. I lost a sister, found a brother, and lost my father. I couldn’t leave my newfound brother here alone. I moved back into my childhood home in January of 2021, and celebrated my first Katrina anniversary back home, evacuating to the same sister, now in Phoenix, for Hurricane Ida.

I did listen to Peaches and find my voice. We lost her in 2018, and though we were distant friends, so much of how I use my voice, especially now that I’m back home, is in honor of her and how much she loved this city. I’ve been on stages and in small rooms speaking for New Orleans’ drifting daughters in tones of grief as well as joy.

On my return, I did what a lot of people are still coming around to: I went to therapy. I was finally confronted with how not-fine I was. Getting up and making lemons out of lemonade is fine for a day when you forget to put gas in your car, so you take the bus and read a book you’ve been putting off. Not for glossing over the trauma of loss and neglect.

After 15 years of searching for myself, I had to find myself in the place where it all started. Healing is a perpetual journey. Thanks to the dynamic nature of life, there is no particular destination. Healing means carrying a first aid kit with the appropriate tools to patch yourself up when you need it.

For me, it was relearning a home that is not the home I left. I am a New Orleanian. I’m uncertain who this “NOLA” creature is. As I’ve said many times before, “New Orleans begins in the bones.” NOLA just doesn’t permeate.

It has led me to advocacy work in climate justice, regardless of the name. In Louisiana. Let what that fight looks like sink in for you. I can’t promise that there will never be another Katrina. Given that I follow what scientists say about climate change, I believe that there will be. Even thinking about it now, a ball of rage forms in my chest that makes me feel like if I tried to channel its energy, it could take a building down. Instead, I channel that into helping my people and being kinder to my planet. I grab my little emotional first aid kit and I get to work.

Join me out there.

Melanie Dione is a wandering daughter of New Orleans who has also found community in our nation’s capital (DC) and the Paris of Appalachia (commonly known as Pittsburgh). When she isn’t advocating for environmental justice, she is writing under the strict supervision of her son, daughter, and two cats.

SEE ALSO:

Healing Is A Fluid Journey: How Hurricane Katrina Changed Me was originally published on newsone.com